Klotzen! Panzer Battles - marko.millojevic

How most powerful German ship was sunk

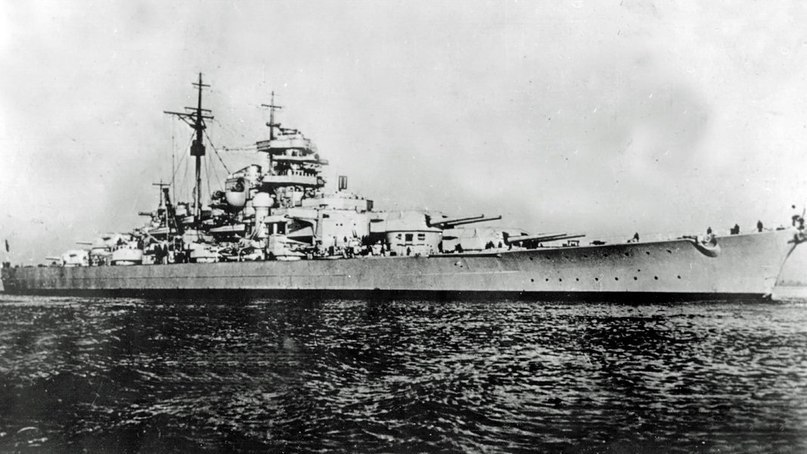

The Bismarck, probably Germany’s most famous battleship in World War Two, was sunk on May 27th 1941. The Bismarck had already sunk HMS Hood before being sunk herself. For many, the end of the Hood and Bismarck symbolised the end of the time when battleships were the dominant force in naval warfare, to be replaced by submarines and aircraft carriers and the advantages these ships gave to naval commanders.

The Bismarck displaced over 50,000 tons and 40% of this displacement was armour. Such armour gave the Bismarck many advantages in protection but it did not inhibit her speed – she was capable of 29 knots. Launched in 1939, the Bismarck carried a formidable array of weaponry – 8 x 15 inch guns, 12 x 5.9 inch guns, 16 x 4.1 inch AA guns, 16 x 20mm AA guns and 2 x Arado 96 aircraft. The Bismarck had a crew of 2,200.

In comparison, HMS Hood (built 20 years before Bismarck) was 44,600 tons, had a crew of 1,419 and was faster than the Bismarck with a maximum speed of 32 knots. The Hood had been launched in 1918 and was armed with 8 x 15 inch guns, 12 x 5.5 inch guns, 8 x 4 inch AA guns, 24 x 2 pounder guns and 4 x 21 inch torpedoes. However, the Hood suffered from one major flaw – she did not have the same amount of armour as the Bismarck. The fact that the Hood was faster than the Bismarck by 3 knots was as a result of her lack of sufficient armour. Within two minutes of being hit by the Bismarck, the Hood had broken her back and sunk.

On May 18th, 1941, the Bismarck and the heavy cruiser Prinz Eugen slipped out of the Baltic port of Gdynia to attack Allied convoys in the Atlantic. Grand Admiral Raeder had already had experience of large warships attacking convoys at sea. Ships such as the Graf Spee, Admiral Scheer (both pocket battleships), Hipper (a cruiser) and Scharnhorst (a battle cruiser) had already been at sea but had found that their power was limited by the fact that they were so far from a dock/port that could carry out repairs if they were needed. Such a difficulty meant that mighty ships such as the Scharnhorst and Gneisenau were loathed to take on a convoy if that convoy was protected by any naval ship. In 1940, both the Scharnhorst and Gneisenau came across a convoy returning from the UK to Halifax, Canada. However, the convoy was protected by HMS Ramillies and neither German ship could risk being hit by a ship that in other circumstances would easily be outgunned by both German ships.

To overcome the fear of damage at sea, Raeder’s plan was for the German Navy to concentrate a powerful naval force in the Atlantic so that there would not be a concern about convoys and their protection. He intended for the Bismarck, the Prinz Eugen, the Scharnhorst and the Gneisenau to operate in the Atlantic fully supported with supply and reconnaissance ships – with such a force, no convoy would be safe regardless of how many naval protection ships they had. However, Raeder’s plan, code-named “Exercise Rhine”, was severely hampered from the start when the Gneisenau was hit by bombs while in Brest and the repairs needed for the Scharnhorst would take much longer than Raeder had anticipated. Regardless of this, Raeder ordered the Bismarck and the Prinz Eugen to sail as planned. The ships sailed on May 18th – but on May 20th, they were spotted by the Swedish cruiser ‘Gotland’ off the Swedish coast and the admiral in command of both ships – Lütjens – knew that such information would be received in London before the 20th was out. He was right.

On May 21st, both ships docked at Kors Fjord, near Bergen. The Prinz Eugen needed to refuel. At night both ships left, and not long after this the area around Kors Fjord was bombed by the British.

To get into the Atlantic, both ships had to pass north of Scapa Flow – one of Britain’s largest naval bases. At this base was the battleship ‘King George V’, the newly commissioned (but not battle ready) battleship ‘Prince of Wales’, the battle-cruiser ‘HMS Hood’ and the aircraft carrier ‘HMS Victorious’. With these ships were nine destroyers and four cruisers of the 2nd Cruiser Squadron. At sea in the vicinity were the cruisers ‘Norfolk’, ‘Suffolk’ ‘Manchester’ and ‘Birmingham’. The battleship ‘Rodney’ was also on convoy duty in the Atlantic.

When the new reached the Admiralty that the Bismarck and Prinz Eugen had left Bergen, Admiral Sir John Tovey, Commander-in-Chief Home Fleet, ordered the ‘Hood’ and the ‘Prince of Wales’ to sail accompanied by six destroyers. The fleet left Scapa Flow on May 22nd. All other ships in Scapa Flow and some on the Clyde were put on short notice. On the same day, German reconnaissance for Lütjens, informed him that all the ships that should have been in Scapa Flow were still there.

This was incorrect as the Hood and Prince of Wales had already sailed – though Lütjens thought otherwise. He was also convinced that the weather was on his side as fog obscured many areas to the west of the Norwegian coast and Lütjens became satisfied that he could get into the Atlantic unseen. Such was his confidence that he failed to keep an appointment with a tanker, preferring to steam ahead to the Atlantic. To boost his fleet, Tovey ordered the ‘Victorious’ to sail on the 22nd May and on the following day the battle cruiser HMS Repulse sailed.

At noon on May 23rd, the Bismarck and the Prinz Eugen entered the Denmark Strait, between Iceland and Greenland. Here, Lütjens met problems. The fog he had expected to cover his fleet did not materialise and his ships were squeezed between the Greenland ice field that extended 80 miles out from south-east Greenland to the north-west tip of Iceland itself. Lütjens was well aware that this whole area had been mined by the British and he had to select his course well. The Royal Navy also knew that the Germans would be forced to sail through a small area of sea and at 19.22 on May 23rd, the cruiser ‘Suffolk’ spotted both the Bismarck and the Prinz Eugen. The ‘Suffolk’ reported her sighting and HMS Norfolk picked this report up. At 20.22, the Norfolk spotted both German ships.

The ‘Suffolk’s report had reached the ‘Hood’ and Admiral Holland, on the ‘Hood’ concluded that there were 300 miles between his ship and the Bismarck. Holland ordered that the ‘Hood’ should steer a course to the exit of the Denmark Strait and the battle cruiser steamed off at 27 knots. At this speed, the ‘Hood’ should have come into contact with the ‘Bismarck’ at 06.00 on May 24th. The ‘King George V’ and ‘Victorious’ also picked up the message but were both 600 miles away and would have been unable to support the ‘Hood’ on the following day at 06.00. The Admiralty remained concerned for the safety of the convoys in the Atlantic as there was always the danger the ‘Bismarck’ might slip away. Therefore the ‘Renown’, ‘Ark Royal’ and ‘Sheffield’ were ordered to sea from Gibraltar to give further protection to the convoys.

The ‘Bismarck’ had darkness on her side and for a couple of hours, the ‘Suffolk’ and ‘Norfolk’ lost touch with the Bismarck. Without their positioning information, the ‘Hood’ could easily have lost contact with the Bismarck. However, by 02.47 on May 24th, the Suffolk had regained contact with the Bismarck. The information sent back by the ‘Suffolk’ led the Hood to believe that she would be just 20 miles from the Bismarck at 05.30 on May 24th. At 05.35, the lookout from the Hood made out the Prinz Eugen and the Bismarck at a distance of 17 miles.

Holland ordered the Hood to turn to the German ships and at 05.45 they were only 22,000 metres apart. At 05.52, the ‘Hood’ opened fire and shortly afterwards was joined by the ‘Prince of Wales’. At 05.54, both the Prinz Eugen and the Bismarck fired their guns primarily against the ‘Hood’.

The Prinz Eugen hit the Hood and set alight some anti-aircraft shells kept on deck. The fire this caused was not particularly dangerous for the ‘Hood’ even though it produced a great deal of smoke. At 06.00 a salvo from the Bismarck hit the Hood. The Bismarck had fired from 17,000 metres and the elevation of her guns meant that the shells that hit the ‘Hood’ had a high trajectory and a steep angle of descent. The Hood had minimal horizontal armour and one of the shells from the Bismarck penetrated the Hood’s deck and exploded in one of her magazines. A massive explosion tore the ‘Hood’ in half. Those who saw the explosion said that the bows of the ‘Hood’ were raised out of the sea before they sank. The ship sank extremely quickly and only three men out of a total crew of 1,419 survived.

After the destruction of the ‘Hood, the Germans turned their fire onto the ‘Prince of Wales’. Her captain, Leach, decided that the best course of action was to turn away under the cover of smoke and, along with the ‘Suffolk’ and ‘Norfolk’ continue to tail the Bismarck and Prinz Eugen.

However, the Bismarck had not escaped untouched by the battle. One shell had pierced two oil tanks. The damage it did to the ship was minimal but it did mean that 1000 tons of fuel was no longer available to the Bismarck as the shell had cut off this supply. Other senior officers on the Bismarck advised Lütjens to return to Germany buoyed by the success against the ‘Hood’. This advice was not listened to.

Lütjens decided to split up the Bismarck and Prinz Eugen. He had hoped to split up the Royal Navy that was doggedly pursuing him alone. In this he failed. As the Prinz Eugen steamed away, the pursuers targeted only the Bismarck. At this point the battleship King George V was only 200 miles away and closing fast. Accompanying the ‘King George V’ was the carrier ‘Victorious’. At 22.10 on May 24th, nine Swordfishtorpedo-bombers left the ‘Victorious’ to attack the Bismarck. Using directions from the ‘Norfolk’, the planes attacked through the cloud and found themselves attacking an American coast guard ship. By midnight the planes had found the Bismarck and attacked. Eight torpedoes were fired at the Bismarck and one hit home amidships. It did no damage to the ship but it may well have undermined Lütjens’ self-confidence as he announced to the ship’ crew that 27 aircraft had been shot down. He also informed Berlin that it was impossible for him to shake off the Royal Navy and that he was abandoning the task in hand to sail to St Nazaire as his ship was short of fuel.

As the Bismarck sailed, she was tailed by the Suffolk, Norfolk and Prince of Wales. Just after 03.06 on May 25th, the Suffolk lost contact with the Bismarck and it was assumed that she was steaming west into the Atlantic. In fact, the Bismarck was doing the opposite – sailing east for a port in Biscay. At 08.00, Swordfish from the Victorious were sent up to look for the Bismarck but found nothing. The Norfolk and Suffolk also drew a blank. What gave away the Bismarck was the Bismarck itself.

For reasons not known, Lütjens sent Hitler a message about his contact with the Hood which took 30 minutes to send by radio. This message was picked up by the Royal Navy. However, the information sent to Tovey was misleading as he was not in a position to interpret the bearing given to him by the Admiralty. The Admiralty also made another error. It failed to use gnomonic charts for its bearings and the King George V was given the position of the Bismarck but it was 200 miles out. This led Tovey to believe that the Bismarck was trying to return to Germany through the Iceland-Faeroes Gap. Through no fault of his own, Tovey was wrong.

The Admiralty did realise its mistake and informed Tovey that the Bismarck was, in fact, making for the Biscay ports. At 18.10 the King George V and other ships turned to the Biscay ports. Finally, the Royal Navy was given the correct course to follow but the Bismarck had a lead on them of 110 miles. The weather also favoured the Bismarck as it was deteriorating and visibility was reduced as the cloud as low. The Admiralty used Catalina flying boats to search for the Bismarck. On May 27th, the Catalina’s finally spotted the Bismarck. This information was given to the Swordfish crews from the Ark Royal which was steaming up from Gibraltar. They took off at 14.30 in rapidly deteriorating weather.

The lead Swordfish spotted a large ship on its radar and fourteen planes dived through cloud for an attack. Unfortunately, they attacked the ‘Sheffield’ as no-one had told them that the ‘Sheffield’ was in the same area as the Bismarck shadowing the giant German battleship. Luckily no damage was done to the ‘Sheffield’.

The Swordfish returned to the ‘Victorious’ to be re-fuelled and re-armed. By 19.10, they were airborne once again. At 19.40 they spotted the ‘Sheffield’, which gave the crews the direction of the ‘Bismarck’ -12 miles to the south-east. Fifteen planes attacked the ‘Bismarck’ and there were two definite torpedo hits and one probable. One of the torpedoes did considerable damage to the battleship by damaging her starboard propeller, wrecking her steering gear and jamming her rudders. Two observation planes saw the ‘Bismarck’ literally sailing in circles in the immediate aftermath of the attack and at less than 8 knots. The attack had crippled the ‘Bismarck’. The only saving grace for Lütjens was that the night had come and the darkness gave him some hint of cover. However, throughout the night the stricken battleship was harassed by destroyers under the command of Captain Vian.

The destroyers shadowed the ‘Bismarck’ and fed her position back to the ‘Norfolk’. The ‘Norfolk’ was joined by the battleships ‘Rodney’ and the ‘King George V’. On May 27th at 08.47, the ‘Rodney’ opened fire on the ‘Bismarck’. At 08.48, the ‘King George V’ did the same. The ‘Bismarck’ fired back but a salvo from the ‘Rodney’ took out the two forward gun turrets of the ‘Bismarck’. By 10.00 all her main guns had been silenced and her mast had been blown away. By 10.10, all her secondary armaments had been destroyed and the giant ship simply wallowed in the water. At 10.15, Tovey called off his battleships and ordered the ‘Dorsetshire’ to sink the ‘Bismarck’ with torpedoes. Three torpedoes were fired at the ‘Bismarck’ and she sank at 10.40. Out of her crew of 2,200, there were only 115 survivors. Only 2 officers out of 100 survived.

The ‘Prinz Eugen’ returned to Brest on June 1st and all but one of the supply ships sent out with the ‘Bismarck’ and ‘Prinz Eugen’ were sunk. ‘Exercise Rhine’ had been a dismal failure for the Germans as no convoy was attacked and her most feared battleship had been lost. For the British, there was much propaganda to make out of the episode even though the ‘Hood’ had been lost.