Oct 6, 2020

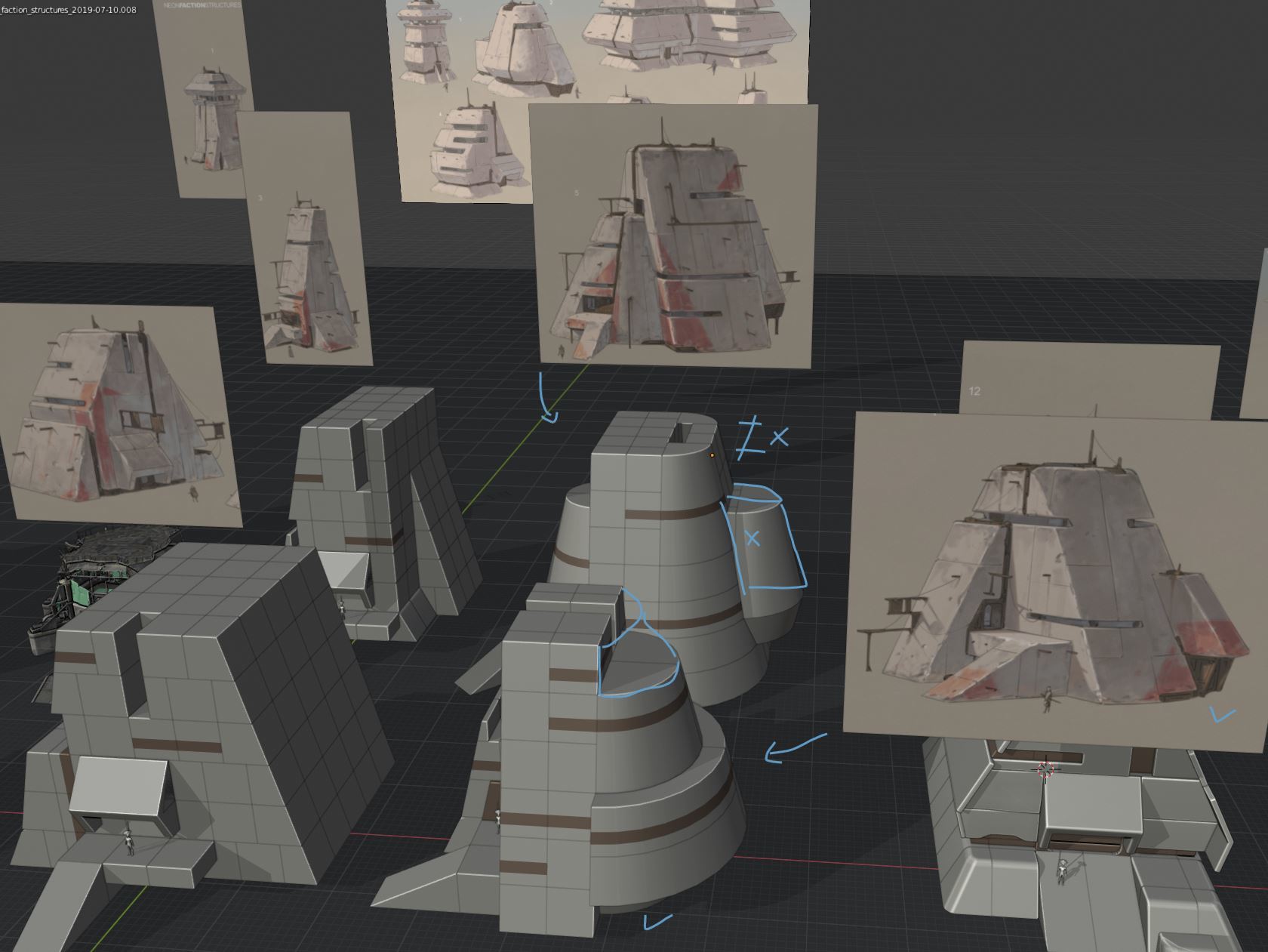

Kenshi - Kenshi_Japan

Out now on the experimental branch only. To opt in to the experimental version, right-click on Kenshi in your Steam games list -> properties -> betas tab -> then choose “experimental”. If opting in, please be aware of bugs and instability.

Please report any bugs or feedback to either the Steam or Lo-Fi forums

Please report any bugs or feedback to either the Steam or Lo-Fi forums

- Fixed deleting saves from new save location

- Fixed bar squads not spawning in Heng due to multiple towns in one zone

- Fixed issue with initial player health if race was changed during character creation